Slowing the Game Down

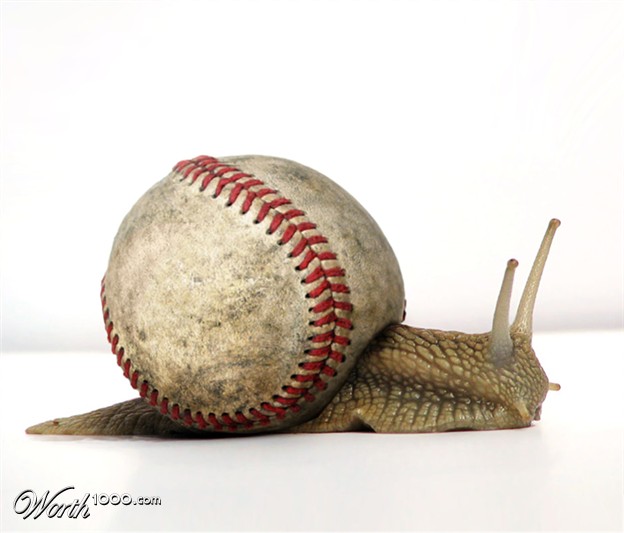

The most important mental game concept for maximizing talent in baseball.

There’s an old saying in baseball that speed never goes into a slump. Not true. In fact, the saying is completely backwards…it’s SLOW that never goes into a slump! Invariably, regardless of the level of competition, from the Big Leagues to Little League, the most important factor for producing baseball players who can perform under pressure is the ability to slow the game down.

Slowing the game down is not a new concept. It’s a key component to what many people describe as “the Zone,” that feeling of optimal experience. Indeed, when many athletes in all sports describe their best performances, they talk about everything moving at a slower pace, their opponents being in “slow motion,” feeling like they had all the time in the world to make their moves.

And likewise, a common theme when performance goes wrong is the speeding up of time. Pitchers get into jams, rush their mechanics, and lose their command with runners on base. Hitters can’t catch up to fastballs that they routinely time with ease when they are in a groove. Position players look lost in the field as they get late jumps on balls off the bat, throws handcuff them, or runners advance as they hold the ball and turn from base to base, unsure of where to throw on bunt plays.

The speed of the game comes into play in a number of situations. For the most part, the game can speed up when:

- A player is playing at a higher level for the first time (MLB debut, AA from A-Ball, high school to college, etc).

- 2. A player enters a game that is in progress (pinch hitter, relief pitcher, double switch) and has not gotten into the flow of the game.

- Pressure is high.

- A player is in a slump or his performance has not met his expectations.

In simple terms, the game speeds up because our perception of time is altered by how we concentrate and by how much information we make automatic. If you can understand how to control the way you focus your attention and automate the important physical skills and mental cues you’ll need to hit, run, catch, and throw, you can slow the game down and improve your performance under pressure.

Focus your Attention

Before discussing the proper way to control your attention, it is first necessary to provide some definition to the term “focus.” The easiest way to explain focus is to compare your mind to a TV set that only gets four channels. We’ll call these channels Awareness, Analysis, Problem-Solving, and Action. Focus can be defined by its scope and direction and these four channels are distinctly different from each other on these dimensions. Scope simply means how broadly or narrowly you are focused. Direction tells whether your focus is external or internal: whether you are paying attention to the outside world or if you’re in your head. When you plot scope and direction on a graph, you can see how the four channels are divided and what kind of scope and direction makes up each one.

The Four Channels of Focus

Awareness

The awareness channel combines a broad focus with an external one. This is that “in the moment” concentration that a quarterback uses to read a defense or a point guard uses to find a teammate filling the lane on a fast break. You use your awareness channel to read and react to the environment.

Analysis

The analysis channel comes from the same broad scope as awareness, but the direction is internal. You use this broad-internal focus when coming up with a game plan, when thinking about many different ideas at once, or when capturing the big-picture from a strategy perspective. Great coaches have extraordinary talents for using this kind of focus to create effective systems for practices and games.

Problem-solving

This channel has a narrow-internal focus. You use the problem-solving channel to work through simple problems (like arithmetic…what’s 15 minus 8? A number immediately pops into your head) or to call up visualization and imagery scenes.

Action

The action channel is the one that is most compelling to athletes. This is the channel you must be on to execute your skills. Imagine that close up shot of Roger Clemens, where you can just see the brim of his cap, his glove, and his eyes in between. He’s locked in on his target and has completed his thought process as he starts into his wind-up. As you can see from the graph, the action channel is narrow and external. There is no thinking taking place here.

Applying the Four Channels to Baseball:

Let’s work through these four channels from the perspective of a hitter and a pitcher so you can see them come to life.

A hitter might go through the following steps during a plate appearance:

- He goes to the Awareness channel to see where the infielders and outfielders are playing him and look to his third base coach for a sign.

- From there, he uses the Analysis channel to review his approach at the plate and thinks about what kind of pitch he should be looking for, given the game situation. Is there a runner on second and nobody out? If so, then he should remind himself to look for a pitch that he can drive to the right side of the field to advance the runner.

- Once he’s done that (and that can take less than a second if he knows what he’s doing), he uses the Problem-Solving channel to see the pitch he wants to hit in his head.

- And finally, he moves to the Action channel and locks in on the pitcher’s release point. The time honored hitting advice of “see the ball, hit the ball” is simply skipping this process and moving straight to the Action channel. You narrow your focus to see the ball and react to a pitch you instinctively recognize as hittable. You don’t have to consciously tell yourself to swing.

A pitcher might use the four channels in the same sequence:

- He uses Awareness by checking with his infielders to see who will be covering the bases. He checks his sign from the catcher and checks the runners. All broad-external behaviors.

- While gathering this information, he uses Analysis to think about the game situation and the pitch sequence he’d like to follow. Is there a runner on second and nobody out? If so, then he should remind himself to try to make the hitter pull the ball on the ground, pop him up so the runner cannot advance, or even strike him out if he gets him to two strikes.

- Once he’s done that (again, this is a quick process), he uses the Problem-Solving channel to picture a fastball in and off the plate to a right-handed hitter that can’t be taken the other way.

- And finally, he moves to the Action channel and bears down on his target. Many pitchers get so narrowly focused on the glove that they don’t see the hitter standing in the batter’s box at all, other than knowing that there is a righty or lefty at the plate.

Using Focus to Slow the Game Down

The connection that brings perception of time together with the four channel model is that time seems to slow down when we remain in External Channels and it speeds up when we are in Internal Channels. Take sleeping, for example. When we sleep, we are 100% internal, there is no interaction with our outside world. And eight hours go by in a flash! We almost never feel like we slept long enough and some of us can feel downright cheated that so much time seems to pass so quickly when we sleep. Compare that to times when we are bored and we engage in “clock-watching.” We get narrow and external on the hands of the clock and they seem to take forever to move.

Another way to look at this is to think about your mind as a movie camera that takes 60 frames per second. If you have .4 seconds from the time that a ball leaves the pitcher’s hand to the time it crosses home plate then you have only 24 frames with which to “take pictures” of the ball and even fewer before you have to decide if you’re going to swing or take. If you’re external throughout the process, then you get 24 pictures of the ball and it moves at its true pace. But, any time your brain is on an internal channel, those frames that should have contained pictures of the ball get replaced with frames of thoughts in your head. If you think too much at the plate (something that happens often in a slump), you might only get 18 pictures of the ball instead of 24. And when a frame is missing a picture, it will jump to the next frame like you’d see in old silent movies in the early 1900’s. Those “jumps” make the ball seem like it is going faster than it is. This is the concept that Ted Williams mastered when he described seeing the individual seams on the ball as it was traveling toward the plate. Most likely, he was able to keep his focus external and saw the ball with every frame available to him. His perception of the ball was that is was going slower than it really was and he felt like he had more time to decide to swing.

So to slow the game down, you can consciously control your focus and place yourself in an external channel. Doing this changes your perception of time and everything around you slows down.

At the plate, that means tracking the ball as soon as you see it in the pitcher’s delivery. Any kind of thought process once the hitter gets into his stance makes time speed up. Everyone has heard about pitchers who hide the ball or have jerky windups that distract hitters from seeing the ball in their hands and are commonly described as “sneaky fast.” Their gun readings don’t register as high as it seems like they are pitching. These pitchers have naturally found a way to limit the time that their opponents see the ball. When a hitter spends too much time on internal channels, it has the same effect as the pitcher hiding the ball…it seems to get on him in a hurry.

Getting external is a bit trickier for pitchers. Pitching isn’t always about simply getting to the Action channel and staying there. When there are runners on base, a pitcher must shift channels between Awareness and Action (broad and narrow) and needs to dip down into Internal channels more often than hitters. There is plenty of science to hitting, but at the moment of truth, it’s reactionary. That lends itself to being perfect for staying on the Action channel. For pitchers, getting external is about developing a rhythm that takes them from focusing on the runners to focusing on the target for the pitch. This is another reason that pace is so important to delivery and mechanics. Stay on the awareness channel and mechanics get rushed or compromised. Move too quickly to the Action channel and that produces tunnel vision. Runners get huge jumps on pitchers who lose track of them on the bases.

Automate Your Thinking

The other way to slow the game down in your head is to make your thinking automatic. The benefits from automatic thinking include less time searching for answers, fewer conscious thoughts that keep you on internal channels, and minimized worries.

When your thinking becomes automatic, you spend less time searching for answers. This represents not a perception of time, but an actual savings of time. By crossing one item off of your to-do list you have more time to allot to executing your task. This can be a time difference that you can feel, which will have ancillary effects on your stress level and confidence. And it is the basic tenet behind the importance of practice. We practice bunt plays, PFP’s, and relays and double-cuts over and over again so we’ll know exactly which base to throw to in a pressure situation with the game on the line. We don’t want to be caught “thinking” in one of those big situations. We want our movements to feel automatic. For a good example of the importance of automatic thinking in another sport, look to football, where each player has different routes, blocking coverages, places to be on the field that must be strictly followed, and there are multiple formations and hundreds of plays to learn.

Not only can automatic thinking save time searching for answers, it can minimize the number of thoughts we have to consciously attend to during a play. Consider all the factors that might go through a pitcher’s head before he delivers a pitch to the plate: “What is the count? What is this hitter’s weakness? What is my strength? What did I throw him the last time I faced him? What inning is it? Are there runners on base? How should I pitch to this guy knowing the game situation and everything else I’ve just considered?” This is where experience comes into play. Experience provides learning moments from real game situations that offer better understanding of how to make decisions based on these questions, and therefore quicker decisions in the future. This is commonly called feel for the game. And feel for the game allows for automatic decision-making instead of spending conscious thought on Internal channels. This has a dual effect on slowing the game down. First, spending less time on Internal channels slows the perception of time. Second, with fewer conscious thoughts, we add more savings to our actual timeline.

Finally, when thinking becomes automatic, it minimizes worry and produces a spike in confidence. Remember that our definition of being on an Internal channel holds for any time we are thinking about anything. Worriers get into their own heads often. Without speaking to the damaging effects of negative thinking and worry and anxiety, in the context of slowing the game down, worrying places the athlete in the wrong channel. Many times this worry has to do with making a good pitch, coming through at the plate with runners in scoring position, executing the physical skills that baseball players pride themselves on. Through practice and experiential learning, pitching, hitting, running and throwing become automatic. A player who knows what to do without having to think about it can relax and just play the game. In that state of mind, worry is minimized, leaving it easier to remain on external channels, which slows down the game.

Slow the Game Down

The most important mental game concept to master in order to maximize talent is slowing the game down. The game slows down on it’s own when you are feeling confident, comfortable, and in control. But during those times when pressure increases or when you find yourself questioning your abilities, there are a few simple keys that can help keep the game from speeding up. Shifting to an external focus is the best way to slow your perception of time. Hitters can do this by improving their tracking skills. Pitchers need to balance their external focus between broad and narrow channels and not every pitcher will find that balance in the same way. But the common thread for pitchers that master the external balance between broad and narrow is developing a rhythm that keeps their mechanics and game awareness in tact. Automatic thinking is another way to slow the game down. Practice, learning through experience, and using confidence are all ways to turn conscious processes into automatic ones. Remember that time isn’t speeding up and slowing down, it’s our perception of time that is changing. That perception is under your control. And it’s your key to performing under pressure.

I found your article very good, especially on the aspect of “pressure”! Especially self induced pressure and how to identify and deal it. Most importantly, switching to instincts’ to relieve the pressure that comes from over analyzing what we are doing!

Willy Mays is quoted as “baseball is a thinking man’s game, and if you’re are not thinking then you are not playing baseball”. Truer words were not spoken, I’m sure he too relied on his instincts. Take the example of his most famous catch, instincts galore, yes?

I enjoyed your analysis of how to deal with pressure and how it stems from over analysis. Willy Mays is quoted as saying “Baseball is a thinking man’s game and if you are not thinking you are not playing baseball”. Well instincts’ for Mr. May’s were never more illustrated then in his most famous catch and make your observation on instincts even more germane to the separation of analysis vs. instincts!

Kudo’s

This may be the greatest baseball article ever!