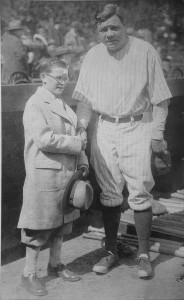

Historical Hitter October 6 1926: Babe Ruth

The World Series is the stage that etches great players into the national consciousness. The Babe set the mark for home runs in a World Series game today at three. In fact Ruth did it twice, 1926 and 1928, in the same park, Sportsman’s Park, and of course against the same team, the Cardinals.

The first home run occurred in the top of the first with two outs was a Ruthian blast that flew out of the Park over the right field roof.

The second home run occurred in the third inning and again with two outs, nobody on base. The ball clears the roof in right center alley and breaks a window across the street some 515 feet away.

The third home run occurred with one on in top of the sixth putting the game well out of reach at 9-4. It was estimated to travel 530 feet, becoming the legendary longest home run in World Series history.

With the facts of the day identified, it is also a great game of mythology as portrayed in the “Babe Ruth Story.” Before the game, The Babe visits a hospital and promises a sickly, bedridden boy, little Johnny, that he will try to hit a home run. Myth and reality merge the Babe does indeed hit three for little Johnny. And little Johnny recovers.

With the facts of the day identified, it is also a great game of mythology as portrayed in the “Babe Ruth Story.” Before the game, The Babe visits a hospital and promises a sickly, bedridden boy, little Johnny, that he will try to hit a home run. Myth and reality merge the Babe does indeed hit three for little Johnny. And little Johnny recovers.

Myth or reality? As the fortieth anniversary of this event neared the Babe Ruth Museum in Baltimore initiated an open inquiry to validate the story. The mythological part of the story is the Babe visiting little Johnny in the hospital. But the real little Johnny did recover. John Sylvester attended Princeton University, served in the Navy, and later was President of the Amscomatic Corporation.

John Sylvester was born in New Jersey, and a huge Yankees fan. His father was the President of the municipal banking division of what now is Citi Bank. Ironically it’s the same Citi Bank that is now Citi Field. Johnny Sylvester was known as the Babe Ruth Kid at the Essex Fells Grammar school. His injuries were sustained during a horseback riding accident during the summer of 1926. As summer turned to fall, his condition worsened, he was diagnosed with osteomyelitis in his skull, at the time thought to be a life threatening illness. Through his banking connections Johnny’s father sends a telegram to The Babe. It stated that the boy is very ill, and could The Babe do something to cheer him up. The Yankees send back a care package of two autographed baseballs, one from the Yankees and the other from the Cardinals. Included was a note from Ruth that read:

John Sylvester was born in New Jersey, and a huge Yankees fan. His father was the President of the municipal banking division of what now is Citi Bank. Ironically it’s the same Citi Bank that is now Citi Field. Johnny Sylvester was known as the Babe Ruth Kid at the Essex Fells Grammar school. His injuries were sustained during a horseback riding accident during the summer of 1926. As summer turned to fall, his condition worsened, he was diagnosed with osteomyelitis in his skull, at the time thought to be a life threatening illness. Through his banking connections Johnny’s father sends a telegram to The Babe. It stated that the boy is very ill, and could The Babe do something to cheer him up. The Yankees send back a care package of two autographed baseballs, one from the Yankees and the other from the Cardinals. Included was a note from Ruth that read:

“I’ll knock a homer for you in Wednesday’s game. Babe Ruth.”

That Wednesday was October 6th 1926, and once the local papers got a hold of the story, the boy miraculously got better. The 1926 World Series ended with the Babe called out trying to steal second base in one of baseball’s most unusual plays. Back in New York, the Babe visits the Sylvester home where the Babe Ruth Kid famously tells the Babe, “I’m sorry the Yanks lost.”

That ball was donated to the museum, and currently on display. Reality was transformed into myth at the movies.

October 6th is known as the Billy Goat game, the loci of the Billy Goat curse.

Myths are very powerful in baseball, both positive and negative. One such long lasting myth is that Abner Doubleday “invented” baseball. These short phrases metaphorical sound bites become the commonly used language to define the game and subsequently, the team’s identity and culture icon. With much help from the Chicago media, the Billy-Goat Curse was born and fermented as a part of baseball lexicon. And it also highlights the power of the baseball curse. So myth becomes reality and reality of each lost game, and each season is memorialized as myth.

One version of the story goes as the following:

Sianis was a long-time Cubs fan. On October 6, 1945, he bought two tickets worth $7.20. One of the tickets was for him; the other one was for his goat. He was allowed to parade with the goat on the baseball field before the game started, with the goat wearing a sign stating “We Got Detroit’s Goat”.

Version two of the story goes as following:

According to an account in the Chicago Sun of October 7, 1945, the goat was turned away at the gate, and Sianis left the goat tied to a stake in a parking lot and went into the game alone. There was mention of a lawsuit that day, but no mention of a curse.

Today the result of the myth is entrenched as part of the team, the invisible 26th teammate that is determined to cause the cubs to lose. Despite numerous goat interventions all have failed keeping the Cubs from winning the World Series. The goat obsession has gone to new heights, and in a “Godfather” movie scene replayed, goat heads make their appearance on iconic Cubs statues and in mail room of Wrigley Field.

The baseball story of October 6, however, is all about a goat — something better found as tomorrow’s kabobs from a food truck. Yet the power of this myth at the most critical event will cause a Cub downfall either in the field or a batter not getting that hit.

This is where the Eddie Grant Monument enters the lexicon. The 100 pound cast bronze plaque last “disappeared,” and left behind. The New York Times reported that three teenagers were seen prying the bronze plaque off the monument. Combined with the lack of success of the Giants in San Francisco and the lost Eddie Grant plaque; the Curse of Eddie Grant was born.

Either the original or another copy of the plaque was found in the attic of the house in Ho-Ho-Kus, New Jersey in the home of a former NY City Police officer whose beat was the Polo Grounds. The home’s new owners found it wrapped in cloth tucked away in a trap door space in the attic. Subsequently the numerous calls and letters from fans and some media to place the monument in San Francisco were rejected with a few of the entrees receiving great levels of distain. The Giants stated that the Eddie Grant plague was a New York event not a San Francisco event. Finally, after the 2002 World Series loss, the Giants front office wore down and confessed:

“Baseball fans are so superstitious, and players are too, so you have to take this stuff seriously. And if by putting up a plaque we can break some sort of curse, who’s to say it’s not the right thing to do?”

The plaque’s recasting, a supposedly simple task, turned into extremely difficult operation. The first version cracked, as did the second, requiring more castings until a complete version was realized. Some two years later on Memorial Day 2006, it was placed near the Lefty O’Doul gate.

As for the curse, on October 28, 2010, Tom Singer of MLB.com was the byline for a story entitled,

“Grant curse no longer weighing on Giants”

As the plaque found in Ho-Ho-Kus, the Mets acquired it. Presently, it’s located inside Citi Field, some 483 feet from home plate and in a way partway between San Francisco and the Argonne Forest. As for the Mets, the plaque’s mythical powers do not seem to affect their win-loss record.

What does all this have to do with hitting a baseball? Simple, batting is all about your state of mind and the undivided attention required to hit Ruthian home runs.