Historical Hitter September 25 1931: Cal McVey

On this day in 1931, baseball again rose to the occasion and performed a Charity Series in New. Unlike yesterday, in 1931 the Dodgers lost to the Giants. The round-robin playoff among New York City’s three major league teams, to raise money for the unemployed, concludes with Brooklyn losing to both the Giants and the Yankees at the Polo Grounds. Again, a near capacity crowd turns out and adds $48,000 to bring the fund to $108,000 (Baseball-reference.com.)

Also in New York, some two-score and one year’s ago, another New York Baseball Hero was honored. (The Mets did somehow figured out to retire the number 41). Coincidently some nine month’s-time before Derek Jeter was born in New Jersey; it was Willie Mays Night at Shea. Traded to the Mets as a means of closing out his career in the City where he started it was quite the emotional ceremony. In a typical Mets lackluster manner, the Number 24 that was promised to be retired and was has yet to be done–along with Gary Carter’s and Yogi’s number 8! It turns out the equipment guys never got the memo either and the number 24 was given to other players not once but twice. Kevlin Torve wore it in 1990. That year he got into 20 games and knocked in just 2 RBI. Torve had an OPS+ of 116 that year, but with so few at bats his career OPS+ was a below replacement level of 78. It’s actually rather disappointing to report this; after all it was the team’s fault and the reporting of it falls on the back of the unsuspecting and undeserving innocent victim Torve. During the 1999-2000 seasons the Mets again suffered from memory deprivation and gave Hall of Famer Ricky Henderson the number – although Henderson wore numbers 14 or 35 in his career. Ricky did his best to honor the number and helped lead the Mets to the Pennant. In his time in Flushing Rickey Henderson played in 152 games and batted a few ticks below 300. Given their inept tradition and noted player mismanagement, buffered by a miracle season or two, the Mets actually Won-One-for-Willie this night beating the Nats/Expos 2-1.

In a more appropriate note, the Hitting Hero is one of baseball first heroes, Cal McVey of the original Boston Red Sox (Red Caps, Red Stockings) of the National Association from 1871 to 1875. On this day in the closing days of 1874 – 101 years before Willie Mays Night at Shea- and during their dynastic run, these Sox had no trouble putting away Baltimore’s nine, 9-1. McVey was the hitting star by hitting two home runs!

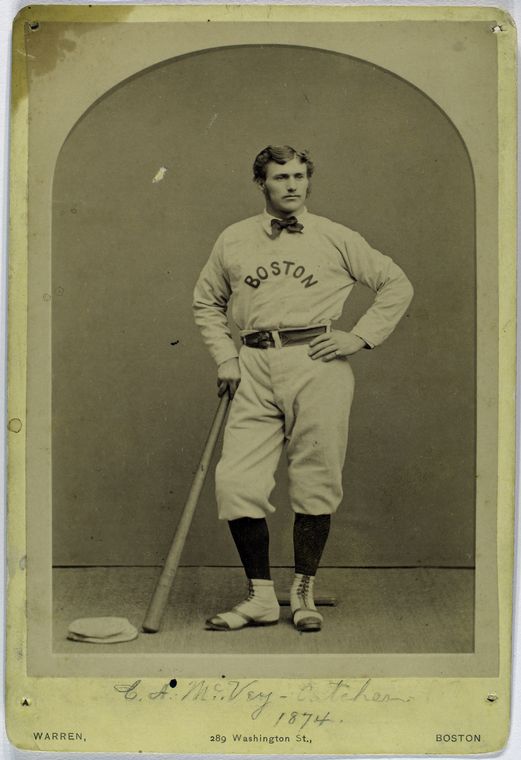

As we can see from his early cabinet photo, he wears the Boston red sox with a sense of honor and pride in repose of calm confidence of a true baseball hero.

As we can see from his early cabinet photo, he wears the Boston red sox with a sense of honor and pride in repose of calm confidence of a true baseball hero.

McVey was one of baseball’s earliest professional stars playing with the Wrights in Cincinnati as a member of the 1869 Reds, then moving to Boston as a stalwart for the Red Stockings, rebelling against the gambling and chaos of the National Association and moving to Chicago in 1876 to help establish the National League. He finished up his stellar career back in Cincinnati for two more years. His four year National League batting average was a healthy .328 and only in his last season he did not hit 300, just coming in short at .297. I find it utterly amazing that he played two of the most difficult positions, catcher and first base in an era with no gloves and was able to even grip a bat with all the punishment his hands took and then to hit well over .300 is remarkable.

This day of multiple home runs was one of the earliest recorded in baseball and the only one his career, as home runs in the 1870s were a rare event.

Throughout his career, McVey was a winner. He played a vital role in these winning teams. Only one team that McVey played on had a losing season, the 1877 Cubs. These Spalding- pitcher-less Northsiders went 26-33 during that infamous year. Overall, McVey’s teams won almost 70% of their games going 383-167 over nine years.

He was one of the game’s best athletes and known for performing gymnastic flip flops after victories a century before Ozzie Smith (given the number of victories, it was a lot of them). His athleticism seems to be actually detriment to his positional career. He played every position and more than once, with none as a stunt. His primary position was First Base with 186 games played there out of a total career of 606, as noted by Baseball-refrence.com. Yet during the Spalding era, he was AG’s preferred backstop. McVey played that position – with no mask, chest protector, glove, shin guards- or even rule 7.13 to protect him for a total of 182 games. On the days when Spalding did not pitch, it was up to McVey to hold down the opponents as the team’s second pitcher to which he did with only moderate success going 10-12 in four years. To compare, in those days Spalding stocked up 252 wins against only 65 defeats. Francis Richter of Sporting Life lists McVey as the best outfielder of the 1870’s– yet records indicate he played perhaps as few as seven games in the outfield during one season. Overall, in nine years he played only 110 games in the outfield.

His career batting average was well over .300 – .348 with a 9 year career OPS+ of 152. In his time in the National Association and then National League, he was league leader in runs scored, doubles, slugging and OPS once; and in base hits, RBI’s and total bases twice. We can see from his record that he was a fearsome hitter of his day.

The box score on this day back in 1874, McVey was stellar: he went 3 for 5 with 2 home runs, 4 RBI’s, and scored 3 runs. McVey out hit his Hall of Fame teammates (G. Wright, H. Wright, Deacon White, “Orator” Jim O’Rourke & AG Spalding that day.

Ross Barnes, McVey’s teammate, who played nine years and hit .360 with more power and had higher slugging numbers. Nevertheless, it remains a mystery why these two, Barnes and McVey, although clearly identified as early heroes of the game are not in the Hall of Fame. The box score is listed below.

| Boston Red Stockings | AB | R | H | RBI |

| G. Wright ss | 5 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Barnes 2b | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| White rf | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Spalding p | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| McVey c | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Leonard lf | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| O’Rourke 1b | 4 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| H. Wright cf 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Schafer 3b | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Totals | 39 | 9 | 13 | 8 |

In those nineteenth-century games played on cow-pasture like fields and when players wore no gloves catcher McVey had two passed balls and two errors, overall the Bostonians had 4 errors. But their Baltimore-based opposition had 9 errors.

In a time when baseball was the only recipient of acts of civic pride, McVey wrote that the city and fans of Porkopolis were baseball crazy, and treated them well. When the team returned from a road trip to the Queen City they all received a hero’s welcome- one fit for a Roman Emperor, as McVey noted:

“There would be brass bands, torches and fireworks, then a big banquet for the players. Once we were met at the railroad station by a horse-drawn bus shaped like a baseball bat, all gilded and draped with flags.”

The big issue for me is why is Cal McVey forgotten? Although elected to the Iowa Sports Hall of Fame, Cooperstown’s scared walls have no spot for McVey. I share this sentiment with Cal’s SABR Bio Project author, Charles Faber, who wrote,

Not many modern baseball fans are familiar with the exploits of Cal McVey, but 19th-century aficionados acknowledge him as one of baseball’s great pioneers.

For me, he was Cincinnati’s greatest baseball ambassadors; he played the game with integrity, honesty, grit and at a very high level. As an Original Red and then a leader on baseball’s first dynasty, the National Leagues initial Pennant winner, and then returning to Cincinnati to finish his career, why have we forgotten the honest and legitimate baseball exploits of Cal McVey?

It seems that he too was been tarnished by baseball’s cardinal sin of game fixing and gambling, however, in McVey’s case it’s only one bad timing, being in the wrong place at the wrong time. The last image of Cal McVey was tainted, and thus could have his entire career been marginalized? As Faber reported:

A final moment of glory came for Cal McVey in 1919 when he was invited to come to Cincinnati as an honored guest at a celebration of the 50th anniversary of baseball’s first professional team. He proudly rode in a festive parade prior to the opening of the World Series between the Reds and the Chicago White Sox.